I admit that it hurts a little—but not entirely—to understand a Spanish meme on Twitter or Instagram. I don’t use a Spanish keyboard on my iPhone. And try talking to other fluent Spanish speakers with Google Translate. I can’t compete.

In short, I probably understand about 30 percent of what’s said to me, and that’s being generous. I religiously use subtitles when watching Narcos: Mexico. To say it’s just embarrassing is an understatement. Finding a solution to my first-world problem ended up with long-term plans for the future.

Straddling Two Worlds with One Language

It’s awkward being multiracial but monolingual. I’m the less than half of US-born Hispanics whose Spanish is forever subpar. I’m also part of the less than half of 1.4 million Filipinos surveyed in 2013 that live in California and do not speak Tagalog, Visayan, or Ilocano.

Pew Research Center data shows that over 60 percent of Hispanic-born citizens in the United States speak Spanish. And U.S. Census Bureau projections found that the share of those who speak only English at home rose from 26 percent in 2013 to 34 percent in 2020.

But 95 percent of all Latino adults see the value in learning how to read and write in Spanish.

So Where Do We Fit In?

So, where does the third of non-Spanish but Hispanic-identifying speakers fit in? There are 10 million Americans that identify as multiracial. What cultures do they identify with best?

My sense of culture is chaotic. Probably not by choice. None of my tattoos match. I feel more like a “Valley Girl” than anything. A language barrier is always an excuse for staying mute on the matter. Growing up in rural Southern California, I never realized just how much I would be missing out by never picking up either of my native languages.

Language Lost, Identity Fractured

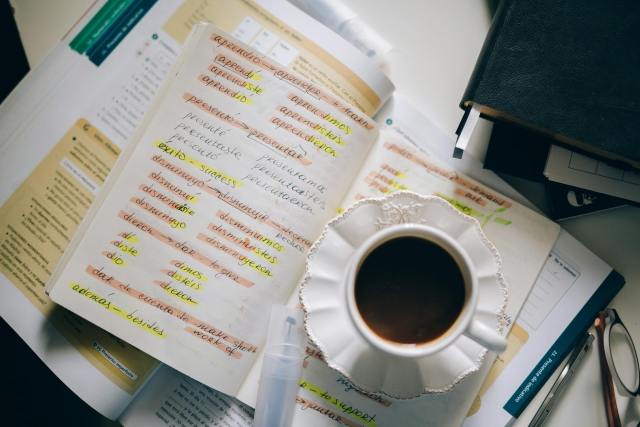

I have a handful of Spanish-English dictionaries that we’ve barely touched. At 29, I’m too old to pick up a second language thoroughly. Eighteen is the cut-off for learning a new language well, according to Scientific American. When faced with the debacle of my monolingualism in public, I usually smile and say that I can’t roll my tongue for an “r.”

Therefore, I’m not going to try.

Trust me, learning Spanish in high school pales compared to someone who has spoken Spanglish their entire life. I yearn to code-switch and never will.

I lack an identity except being a third-generation American, which is less than impressive these days.

The Cultural Disconnect Is Real

Being light-skinned yet part of a multitude of beautiful yet underrepresented groups made for an interesting upbringing. It shows a stark difference between first-generation immigrants and the latter.

People who speak Tagalog or Spanish—primarily Spanish—will come up to me to strike up a conversation. In Costco, at the DMV, whatever. The blank stare they get in response that turns into a nervous laugh is always met with an eyeful of disappointment when realizing that I’m entirely white-washed.

“Why didn’t your parents teach you any other languages?” — the general question I feel — masked behind a blank stare with a hint of disdain. The ability to speak the Ilocano dialect was never something my maternal grandmother taught to anyone. My great-grandparents took the language with them when they passed. My mom never knew her father, a Hispanic and native military man who died before birth.

My paternal grandmother and my older family on her side speak Spanish, while the younger generations know very little. I could never understand why until I got older.

A Legacy of Survival

People seemingly tend to look down on others who share their heritage but lack the native language. Statista found that 7.3 million Americans in multiracial relationships identify as Hispanic. But you have to consider the term itself is a colloquial monolith.

I didn’t choose only to speak English. Colonialism did that for me. Not every person gets a chance to hold onto the cultures that represent their identity. All I can continue to do is look on with envy at those that can migrate their entire conversation to a different language like nothing. And I can also advocate for change.

My entire racial identity, my whole family, gentrified themselves over a century to assimilate and survive. The part left the Philippines for Hawaii before World War II. The rest fled Sonora, Mexico, and settled in the most significant Yaqui indigenous settlement in all of Arizona.

With some long-winded, extensive research, I’ve realized that both my mom and dad’s parents felt it was better to keep all aspects of culture at home and exude as much whiteness as possible. I developed a sense of fractured yet eloquent cultures through other avenues: vast amounts of literature, food, music, and art.

Rewriting the Future

I hope to instill those values in my future children—while allowing them to learn more than what English has to offer. While I may never really know where my indigenous roots lie because colonialism took those languages from my generation, I don’t plan on leaving my family to figure out their identities on their own.

Thirty years ago, there wasn’t a push to have bilingual children like there is now. Interracial marriage is still a relatively new concept. It was a survival tactic for survival in a nation ruled by white, wealthy men. When I look into U.S. census records, I don’t see a sole family name there. The fact that immigrants had to swallow their cultures to fit into America’s bubble is egregious.